December 2021

Cynthia Weber, PhD, on behalf of IEEE Brain

Guidelines that consider societal and cultural impacts of neurotechnology are crucial for ensuring responsible innovation in the field.

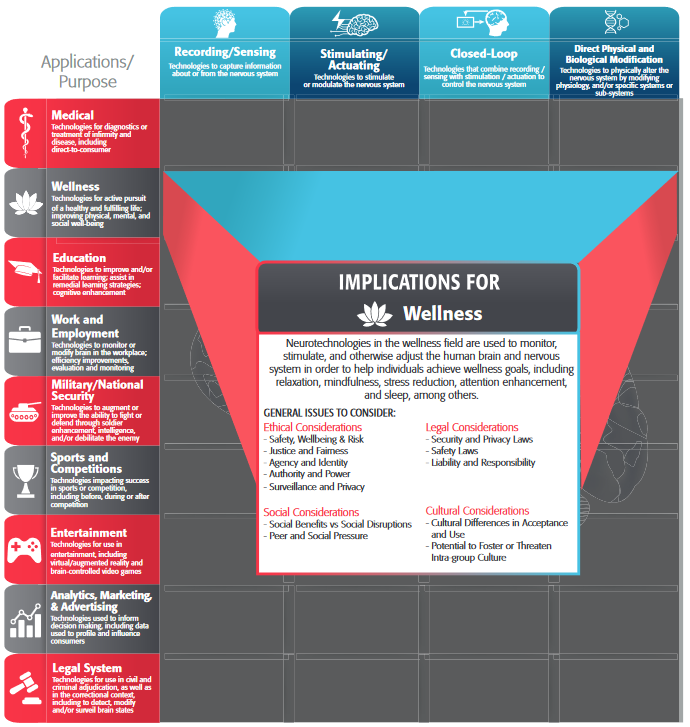

Ethical considerations have not always been of primary concern in the development of technology. However, the need for ethical standards and guidelines for neurotechnology has received significant support with multiple efforts underway that aim to sidestep past mistakes by preparing for future development and use cases. The challenge lies in identifying the complex social, legal, and cultural issues tied to how neurotechnologies will be accessed and implemented once released into the world, and the associated safety, privacy, and long-term consequences of its use. For many people, the brain is intimately connected to one’s sense of self and personal identity—our thoughts and emotions, for example. Consequently, neurotechnology devices that intervene with the brain, whether for medical treatment, wellness applications, or entertainment, may pose unique perceived risks for the user. This is also the case when neurotechnology has the potential to be implemented in employment, legal, or educational contexts. In all these scenarios, ethical considerations are interwoven within layers of consent, data access and control, and possible manipulation.

As part of an ongoing effort, the IEEE Brain Neuroethics Subcommittee has been working to develop an IEEE Neuroethics Framework and associated documents that explore the ethical, legal, social, and cultural issues (ELSCI) generated by neurotechnologies when used in specific applications. In partnership with the International Brain Initiative (IBI), Global Neuroethics Working Group, the team put together a workshop on 28 September 2021 to share five of these documents—examining neurotechnology in the contexts of medical applications, wellness, work and employment, entertainment, and legal systems—with a group of international stakeholders.

The primary goals of the workshop, “Integrating Neuroethics into Neural-Engineering Efforts,” were to initiate cross-cultural discussion on the ethical aspects associated with neurotechnology use in these areas in order to gather preliminary feedback on the work that has been undertaken for each of those applications as part of the IEEE Brain Neuroethics Framework, and also identify key experts from major global regions in each application and ELSCI domain.

“The workshop allowed us to bring more visibility to the framework for our international audience,” says Laura Cabrera, Associate Professor in the Center for Neural Engineering at The Pennsylvania State University and Chair of the IEEE Brain Neuroethics Subcommittee. Karen Rommelfanger, Associate Professor of Emory Neurology, Director of the Neuroethics Program at the Center for Ethics, and an IBI co-host for the event, echoes this sentiment. “This was a valuable opportunity to discuss cultural elements related to the deep ethical and legal analysis the IEEE Brain Neuroethics Working Groups have been doing over the past few years. For the IBI Neuroethics Working Group, we appreciated the opportunity to engage the engineering community in neuroethical issues in very applied contexts,” Rommelfanger adds.

More than 40 participants with background expertise ranging from engineering, law, neuroscience, philosophy, and ethics, as well as the regulatory and commercial fields, gathered as a group and in smaller breakout sessions to discuss the shared documents, focusing on key ethical, legal, and regulatory considerations as well as social and cultural concerns. Other objectives of the event included broadening understanding of the scope of stakeholder involvement, i.e., who in addition to engineers and engineering companies would be using this framework and at what process of design and development, along with examining best ways to implement practical guidelines for the field.

In this vein, discussion ensued as to whether neuroengineers face different ethical issues than neuroscientists and how this might be reflected in the recommendations. Participants were thoughtful in their responses as some noted that although ethical issues may be common to both engineers and scientists, the considerations may be different dependent on the nature of their work, for example, design implementation versus finding the cause of a phenomenon. Others responded that as neuroengineers have striven to develop new devices, they might not always have been mindful of the impact of their technology on the human dimension and the problems that might ensue from use of the devices. “We were not able to come to a conclusion, but there are likely interesting and important differences in degree more than kind of neuroethics issues,” Rommelfanger says.

The Matter of Culture

“Ethical, social, and legal aspects always have been considered in the study and discussion of ethics for science. However, cultural aspects also have to be considered because everyone knows that concepts of the human being are directly associated with the brain but the ways of thinking about that connection may differ by culture,” says Sung-Jin Jeong, Principal Researcher with the Korea Brain Research Institute and IBI co-host of the workshop. These differences in cultural perspectives led to important insights in many of the working group applications. One of these was recognition of the value of community versus individuality, both when it came to data capture (e.g., would an individual’s data inadvertently grant access to that of his/her family or community) as well as public health and workplace privacy (e.g., willingness to grant access for the good of the whole rather than prioritizing oneself). In some cultures, the work environment and employee/employer expectations could potentially lead to more acceptance of neurotechnology and data access as part of one’s performance, whereas in others, individual privacy demands may override such initiatives. Peer pressure, the desire for and value of self-improvement, and entrenched competitiveness within some societies might also lead to easier integration and acceptance of neurotechnology in the workplace as well as educational contexts.

In addition, concepts of wellness and recreation differ across cultures, including spirituality as a wellness component and the value of collective identities. These, in turn, may affect how and why neurotechnology may be accepted or rejected, as well as how it is used. Gaming, a significant focus of the entertainment neuroethics document, was noted to be the largest entertainment industry in the world—one that already is known for its propagation of certain cultural identities. How that circumstance might be further entrenched by the addition of neurotechnology in this sphere warrants concern. Ideas of fairness also differ among cultures, with some equating it to gaining an advantage over another and others prioritizing access for all. Issues of socio-economic status and associated limitations to wellness or medical neurotechnology should also be a consideration when addressing global access.

Legal and Regulatory Concerns

Medical tourism and the lack of regulatory oversight have the potential to create pockets of neurotechnology access in some global regions, while stricter regulations in others may delay technology rollout. A key point was made regarding the ethical and cultural quandaries posed when considering that some global regions tend to be technology users with only limited means to create, while other regions hold prominence in neurotechnology development and distribution.

From a legal perspective, although current use of neurotechnology is limited across global systems it will be imperative to have standards in place regarding accuracy of neurotechnology used for evidence. Awareness of the rights of users in court settings and clinical trials (e.g., on prison populations) and recognition of inherent technology bias should be in place to limit coercive use of neurotechnology (e.g., to identify psychiatric disorders and criminal tendencies or require procedures for release).

Neural data, and how it is gathered, stored, and used, raised flags across the working group discussions—from legal systems to wellness and entertainment. As noted, some cultures may be more open to the gathering of personal data as part of employment than others. Regions such as the European Union and Japan are instituting targeted agencies to handle questions of personal privacy and protection. The compilation of neural data, perhaps unknown to the user, through use of wellness and entertainment neurotechnology poses unique ethical concerns due to limited oversight and regulations. Medical neurotechnology used for medical purposes, in contrast, appears to have the most robust regulatory procedures in place, although there is significant variance by country and region, and in some areas, professional conduct serves as a moral guideline for ethical use. However, in cases where such neurotechnology is used outside of established practices, there is a regulatory gray area globally.

Looking Toward the Future

As the IEEE Brain neuroethics project moves forward, a number of potential objectives emerged from the workshop. One idea was to reframe the conception of ethics as a regulatory hurdle and instead view it as fostering responsible research and innovation. Another idea was to reframe the conception of engineering challenges as socio-technical ones. There were also calls to expand thinking around the scope of neurotechnology applications, as it will likely be used in combination with technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) in practice. Exploration of neurotechnology in applied contexts through case studies, an area that the IEEE Brain Neuroethics Working Groups have in progress, was identified as a necessary component of the framework. Finally, it was made clear that this type of international collaboration was only the first step in exploring conversations about neuroethics and growing stakeholder participation. “I hope our product is not only for scientists and engineers but also for the public and policy makers,” Jeong says. “For that to happen, we need to consider several ways to deliver this content to different audiences appropriately and develop the methodology by collaboration.”

“Collaboration in the international sphere of neuroethics needs to work toward inclusivity, cross-sectoral, and public engagement,” Rommelfanger states. “Our group is working to create an international neuroethics strategy in the context of the IBI and would really appreciate collaborating with the IEEE Brain Neuroethics Working Group on developing a bank of use cases for ethics in a variety of contexts, similar to those outlined in the Neuroethics Framework matrix.”

Later this year, a group will be launching a virtual and international neuroethics think and do tank, and the Institute of Neuroethics (IoNx). The Global Neuroethics work will be housed under the umbrella of IoNx. “We were driven by an urgent need to generate more action-oriented solutions to today’s and tomorrow’s thorniest and unaddressed neuroethical issues,” Rommelfanger says. “We aim to involve many IEEE Brain members to scope our projects and collaborate on aligned efforts.”

In the future, the IEEE Brain Neuroethics Subcommittee hopes “to increase international partnerships that allow us to leverage the implementation of practical neuroethics recommendations and guidelines with wider acceptability and usage across different applications of neurotechnology,” Cabrera adds. More information about these efforts and how to become involved can be found here.

Acknowledgements

This collaborative event was organized by IEEE Brain and the International Brain Initiative and supported by the Korean Neuroethics Research Project and by the National Research Foundation of Korea.